“And am I born to die, / to lay this body down? / And must my trembling spirit fly / into a world unknown?”

Is this the beginning of a Christian hymn? Surely not! Are you serious?

You bet your bottom dollar I am!

We’ve been tapping into the rich trove of the “shape-note” musical tradition at All Saints —you can look it up online in various places. Two of the chiefest geniuses of this tradition are (1) the way in which these hymns are composed “for the people of God to sing” and (2) the way in which they are composed for the people of God to sing “in harmony.” The parts are written for the full range of human voices, not merely for professional pop-star-grade humans who can reach supra-human levels of song. They, also, are written for actual harmony —harmony that breaks through the simplicity of pop-music’s “1-3-5” style of doing harmony (which means every harmony line basically follows the melody, differing only in degree of note —-meaning the goal is to make the voices perpetually sing a power cord, it reminds me of a line from Jersey Boys “thirds and fifths”). “Actual harmony” means the voices working in concert but with mutual melodic parts. To keep the entry brief, my friend John Ahern explains this better here. [watch it, then rewatch it, then share it].

The song “Idumea” or “Am I Born to Die” (watch Tim Eriksen’s and Cassie Franklin’s excellent recording here, or listen to the full SATB version from the Sacred Harp folks in Ireland here) originates as a folk melody from somewhere in England (Isaac Watts recuperated it and set it to his own words). Later Isaac Watts’ words were replaced with words by Charles Wesley (one of my heroes —we share a birthday with Brad Pitt). It is Charles Wesley’s words under which the song is famous. This song draws it theme from the book of Job, and thus achieves its title, “Idumea,” as Job was an Idumean king.

It is the song of Edom (Idumea is the Latin form of the Hebrew “Edom”): what’s the point of life? What happens when I die? Was I just born to perish? What do good things mean if they fail after death? Certainly, there’s gotta be more after death —but what? Look, where’s the Judge? I want to talk to Him.

Job has suffered at the hands of the Devil, he is struggling to discern God’s inscrutible goodness amidst life’s suffering, and his three “friends” have turned their counsels against him —seeking to scapegoat and blame him for the woe. Job, faithful but broken, refuses to become the scapegoat. He appeals to a greater and higher court “I know that my redeemer lives, / and that in the end he will stand on the earth. / and after my skin has been destroyed, / yet in my flesh I will see God; / I myself will see him / with my own eyes—I, and not another. / How my heart yearns within me!” (Job 19:25-27).

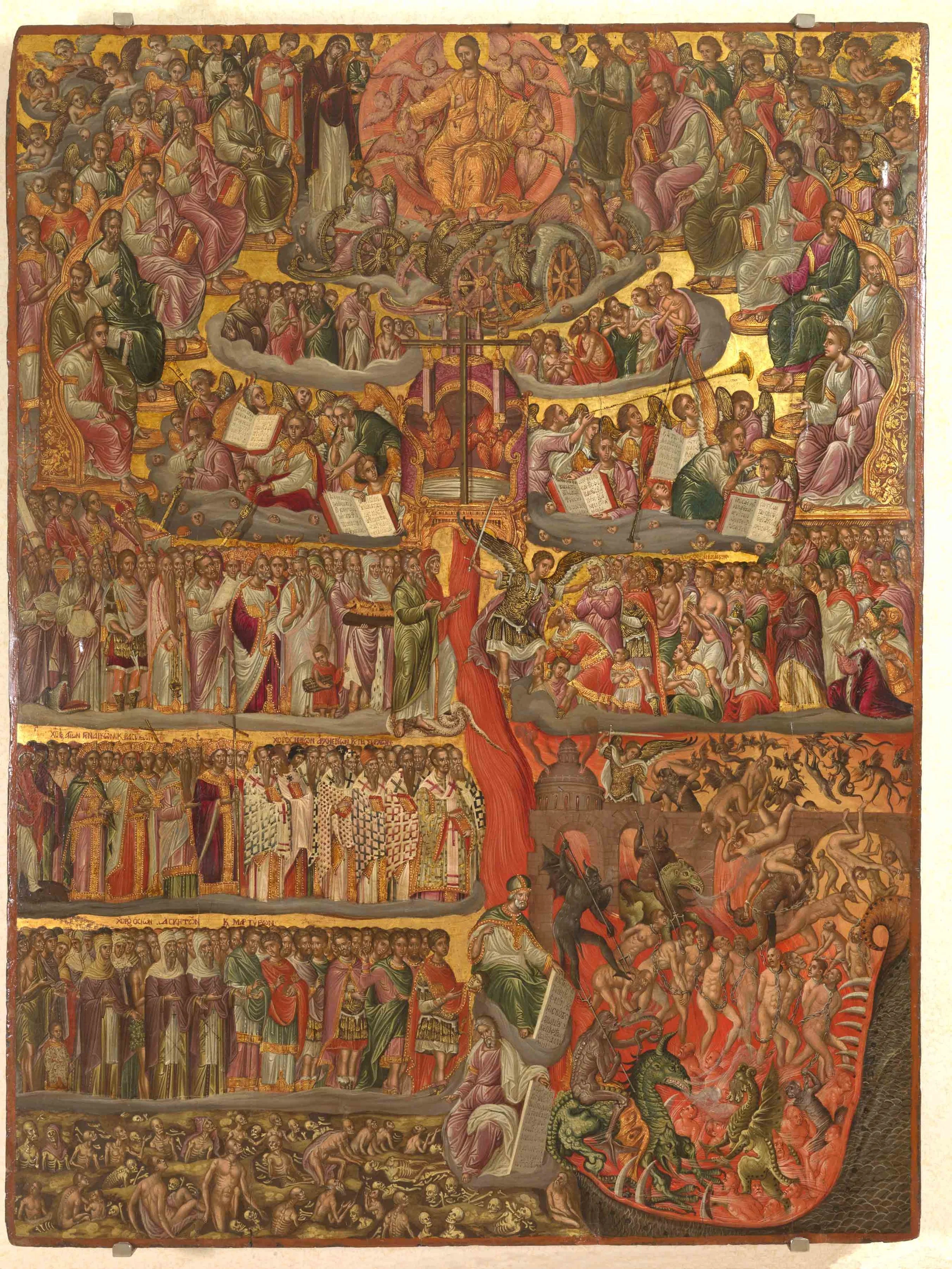

And that’s where the song ends: “Waked by the trumpet sound / I from my grave shall rise / And see the Judge with glory crowned / And see the flaming skies!”

It is a song about the common destiny of all humanity, as we proclaim in the eucharistic liturgy: “bring us with all your saints into the joy of your heavenly kingdom, where we shall see our Lord face to face.”

It puts to music both the common destiny of mankind (standing before the face of Jesus) and the hope of all those who are baptized into Christ “and see the Judge with glory crowned.” It also exposes the condition of our hearts as we sing. It leaves us, so to speak, standing in the presence of the future: “what do I think about standing before the Judge in glory?” It leaves that question for us to walk with the Spirit in our following of Jesus.

It is evangelical: are you born to die or are you born to live forever with the Lord under a flaming sky?